By Hayley Mortimer, BBC File on 4

BBC

BBCAn ex-police officer who claims to save children from human traffickers has faked stories to raise money for his charity, the BBC has discovered.

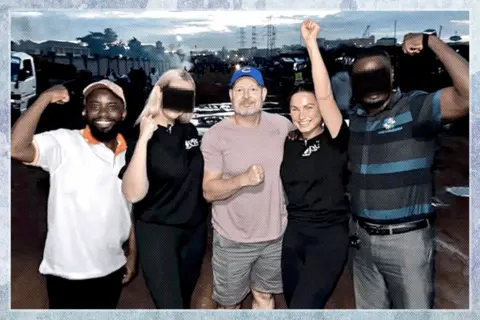

Adam Whittington, founder of Project Rescue Children (PRC) says he has helped more than 700 children in countries including Uganda, Kenya and The Gambia.

But BBC File on 4 has found that some of these children have never been trafficked, and that funds raised – sometimes with the help of celebrity supporters – have not always reached children in need.

PRC has described our allegations that it does not support children as being “completely without merit, misleading and defamatory”.

Our investigation shows Mr Whittington, a British-Australian citizen, has misled donors in a variety of ways – including by raising funds for a baby supposedly rescued from people traffickers, who has actually been with her mother all along. The mother, who lives in poverty, says she and her daughter have never received any money from PRC.

Mr Whittington started working in child rescue two decades ago, after leaving the Metropolitan Police.

He set up a company retrieving children taken abroad by a parent following custody disputes, but later switched his attention to trafficked or abused children.

Both his and PRC’s social media pages have accumulated 1.5 million followers and attracted celebrity support, thanks to their shocking and sometimes disturbing content.

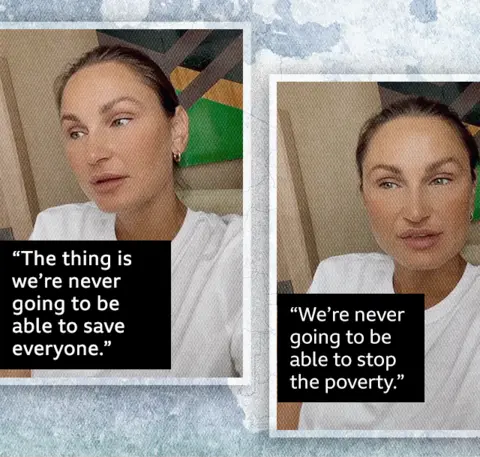

Sam Faiers from ITV’s The Only Way is Essex became a PRC ambassador, and last September was taken to Uganda to meet orphaned and destitute children.

While there, she appealed to her millions of fans to donate and ended up raising £137,000 ($175,000) to build a rescue centre and cover its initial running costs.

It was this fundraising drive that gave me the first real sense that something was amiss.

In the weeks after Sam Faiers’ total was announced, allegations against PRC began popping up on social media, with former ambassadors and directors alleging financial mismanagement and suggesting stories about children were being fabricated.

Less than half of the money – £58,000 ($74,000) – that donors believed would fund the construction and running costs of the proposed rescue centre, was sent to PRC’s Ugandan partner organisation, Make a Child Smile.

Its founder, Alexander Ssembatya, who has apologised to donors, told the BBC he believed the rest of the money had been “eaten by Adam Whittington and PRC”. Construction work was on hold because of a lack of funds, he added.

Sam Faiers told the BBC she was “deeply appalled” and “heartbroken” to learn that not all the funds raised had reached the children and urged Mr Whittington to “do the right thing and release the remainder of the funds immediately to where they are so desperately needed”.

PRC said the money provided was sufficient to complete construction of the rescue centre, and told the BBC it had now withdrawn from the project, accusing Mr Ssembatya of refusing to sign a contract and mismanaging funds.

It said the remaining money had been spent on other children in Uganda and the Philippines.

Charity claims to save children from trafficking and abuse but File on 4 has found that unsuspecting children are being used as props and the rescue centres have no children.

Listen on BBC Sounds now, or on Radio 4 (Tuesday 16 July at 20:00 and Wednesday 17 July at 11:00)

Watch the story on BBC iPlayer, or on the BBC News channel (Saturday 20 July at 13:30)

Although efforts to establish a rescue centre in Uganda fell flat, PRC already claimed to have operations up and running in other African countries, including Kenya.

Since 2020, Mr Whittington has told detailed and distressing stories about the children he has allegedly supported at PRC’s Kenya rescue centre – including siblings who had watched their parents being butchered by traffickers.

Within weeks of launching a sponsorship programme, PRC announced that all 26 Kenyan children pictured on its website had been sponsored.

The rescue centre is in a remote location on the outskirts of the city of Kisumu, which made verifying its existence difficult.

So in April 2024, I travelled with a BBC team, escorted by a police officer, and found the property – supposedly run by a woman known as Mama Jane.

I discovered Mama Jane was an elderly lady called Jane Gori, who lived in the house with her husband. We didn’t find any children, rescued or otherwise.

But I did find out that her son, Kupa Gori, was PRC’s director in Kenya and he had brought Mr Whittington to visit her home.

Mr Whittington uses pictures of improvement work PRC has funded at Mrs Gori’s house to convince donors he is running a rescue centre. Mrs Gori said she had no idea that her name, her house and her photograph were being used by PRC.

Nearby, I met a farmer called Joseph, whose two sons and a granddaughter have featured on the PRC website, described as orphaned, homeless, or victims of trafficking or exploitation. But none of this is true.

Not long after the photographs were taken in 2020, Joseph’s son Eugene died. But his picture remained online until at least February this year. According to PRC’s website, people continued to sponsor him.

Joseph says he has never received any money from PRC, adding: “It pains my heart that someone is using the photos of my child for money we did not get personally.”

When we put our findings to PRC, it told us that it stands by its claim that Jane Gori’s home is a PRC rescue centre that cares for children. It said that all funds for work carried out there were submitted to the Australian Charity Commission – where it was registered.

It did not respond to our question about the misuse of photographs of Joseph’s family.

The next case of deception I uncovered started in 2022, when Mr Whittington claimed to have carried out a dramatic rescue mission – saving a newborn baby from the clutches of traffickers in a busy marketplace in The Gambia.

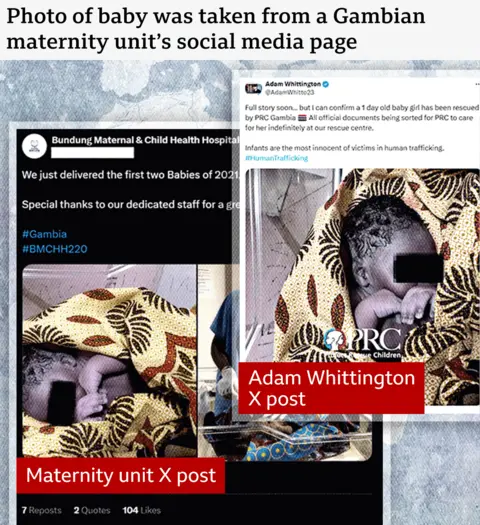

On the morning of 17 December, his team chased two men who dropped a basket as they ran, he said. Inside was a newborn baby, whom he named Mireya. Mr Whittington posted a picture of her wrapped in a gold-coloured blanket.

To give the story further credibility he told his followers he had adopted the baby and said she was being looked after at PRC’s rescue centre in The Gambia.

He told his UK director Alex Betts the same story and asked her to adopt the child with him.

Ms Betts, an online influencer, hoped to bring the baby back to the UK. An online fundraising campaign was launched, along with a sponsorship programme.

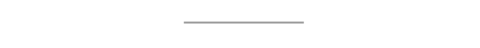

In March 2023, Ms Betts visited the girl she thought was Mireya and took photos and videos of herself playing with a beautiful baby girl. The footage went viral – seen by more than 40 million people.

After Ms Betts arrived back in the UK, Mr Whittington asked her to sign a non-disclosure agreement that would have prevented her saying anything publicly about PRC. She did not understand why and raised concerns.

Then PRC terminated her contract on the grounds, it said, that she was “exploiting children for social media gain”. Ms Betts stopped receiving photo and video updates about Mireya and Mr Whittington attacked her online, falsely branding her a drug addict and alleging, again falsely, that a warrant had been issued for her arrest in The Gambia.

Ms Betts says she was recruited to PRC to “bring social media attention to the organisation”. She rejects the claims against her and says she has always acted “with honest and pure intentions”.

When Ms Betts decided to google “Gambia newborn baby” she discovered the photograph of the baby in a gold blanket was of another child. It had been posted on a maternity unit’s social media page two years before Mireya’s “rescue”.

PRC told us a member of staff had misguidedly used this image because they didn’t want to reveal Mireya’s identity, and that the PRC board had subsequently apologised publicly for any confusion.

The BBC has found no evidence that the marketplace rescue ever happened. But Ms Betts had met a baby – so who was the child?

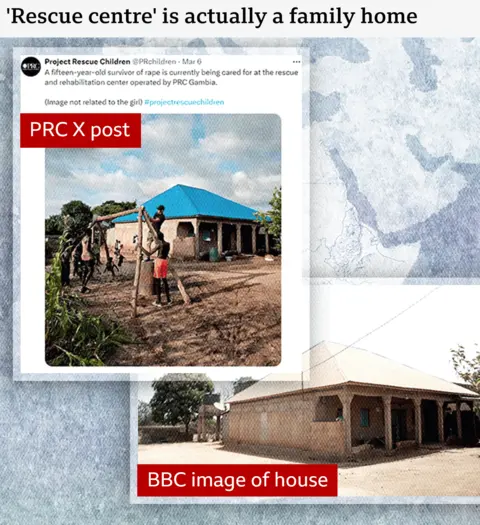

In May 2024, a year after Ms Betts had posted her viral video, we travelled to The Gambia. Our first stop was the location of PRC’s supposed rescue centre.

But, just as we had found in Kenya, it was not a rescue centre and no rescued children had ever lived there. The man who owned the property told us it was just a family home.

His name was David Bass, the father of Ebou Bass, who had been recruited as PRC’s director in The Gambia. He told us that PRC fixed his roof and installed a fresh water supply. Again, Mr Whittington posted images of this construction work on social media and the PRC website to support his claim to be running a rescue centre.

Mr Bass senior told us he did not know the work on his home had been funded with money raised for the renovation of a rescue centre.

We were told the baby known as Mireya lived in a nearby village. Our search took us to a small compound, where we saw a toddler we recognised immediately from Ms Betts’ videos.

The child’s arms were covered in sores caused by a bacterial skin infection, as her mother couldn’t afford the medication she needed.

She told us her baby had been born and raised in the village and that she had been approached by Ebou Bass when her daughter was three months old. He had told her there were people who wanted to sponsor her baby, she said, so she had allowed him to take the child to meet Ms Betts.

She was amazed to hear the stories being told about her daughter online. She said she had never received any money but had been given some groceries on a few occasions.

Ebou Bass, who is no longer PRC’s director in The Gambia, acknowledged that Mireya’s story was false and that the rescue centre was his family’s home. When challenged, he said it was Mr Whittington’s idea to say they had rescued a baby from traffickers but that he had gone along with it because the child they had used as a prop was very poor and he had hoped she would receive financial help.

Lamin Fatty, from a Gambian organisation called the Child Protection Alliance, is now working with the country’s authorities to investigate Mr Whittington and PRC. He says multiple laws may have been broken in this incident.

PRC insists Mireya’s story is true and told us she was rescued by PRC in collaboration with the Gambian authorities. It has invited the BBC to carry out a DNA test on the child we found. It maintains the Bass home is a PRC rescue centre and that Mireya wasn’t at the property because she was overseas visiting relatives.

Adam Whittington served in the Australian Army before joining the Metropolitan Police in 2001, where he worked for at least five years.

We have not been able to find out what has happened to all the money raised for PRC or where it is being spent – Mr Whittington has set up companies and charities in multiple countries, many of which have never filed any detailed accounts.

But we do know some donations haven’t reached their intended targets.

The BBC has found that, in 2022, the UK’s Charity Commission rejected an application to register PRC as it had not demonstrated it was exclusively charitable and had failed to respond to what the commission described as “significant issues” with its application.

Mr Whittington also has other charitable organisations registered in The Gambia, Kenya, Ukraine and the Philippines.

PRC was a registered charity in Australia until we told the Australian Charity Commission about our investigation. Its charitable status has now been revoked.

Adam Whittington is currently living in Russia. He didn’t respond to our request for an interview.

Since we started our investigation, some content has been removed from PRC’s website and Mr Whittington has been banned from Instagram. He instructed solicitors in Kenya to block our investigation from being broadcast, though they have not succeeded. He has launched an online campaign against the BBC, calling me a “rogue journalist”.

On his remaining social media I can see he is currently travelling back and forth to the Philippines – raising money for a rescue centre and claiming to rescue children. And he says he will soon be expanding PRC into South Africa.

Additional reporting: Kate West, Katy Ling and Melanie Stewart-Smith